Glass has proven to be one of the most inevitable materials for the fast-emerging field that involves fabrication of micromanipulation smart devices.

Why glass and what are the possibilities?

It has a desirable optical and good isolation property [1], [2], which in addition to their biocompatibility, chemical stability, hydrophilicity, and optical transparency, makes them suited for various applications ranging from Optical/Bio-MEMS, micro-actuators, micro-sensors, and the Lab-on-chip device. The development of microfabrication in glass techniques over the years enabled different microcomponents and applications ranging from microfluidic (microchannels) [3], [4], [5], [6], optical (optical alignment, waveguide, and positioners) [7], [8], [9], [10], mechanical parts (nozzles, gears) [11], [12], [13], [14], micro-actuators [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [17], [21] and sensors [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31].

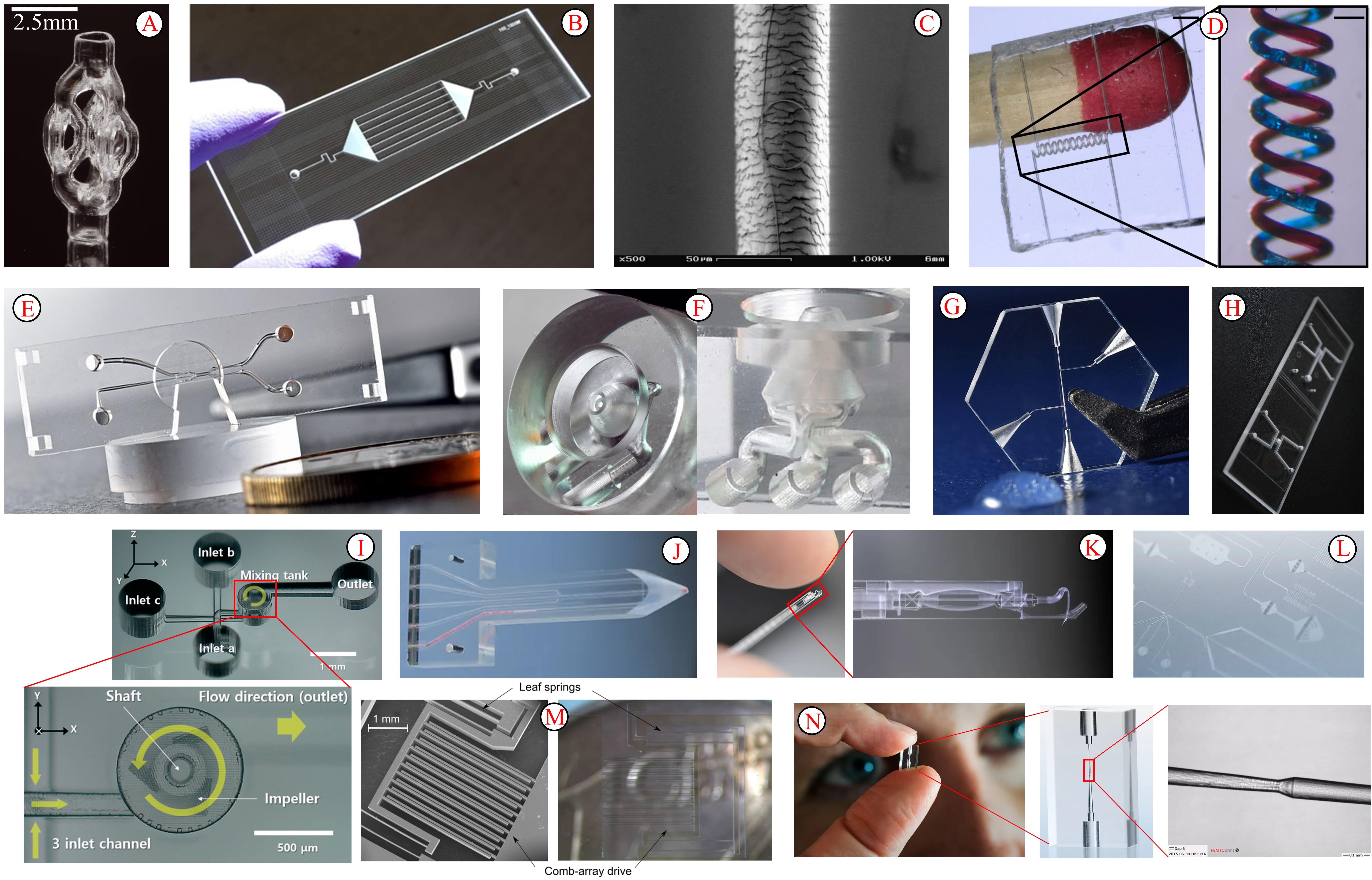

Figure 1. Different 3D miniature devices and monolithic microstructure fabricated in glass A) Volumetric 3D printing of silica glass with microscale computed axial lithography to

fabricate a 3D transparent and complex microfluidic structure, having trusses and lattice with minimum feature sizes of 50µm, [32], B) Microfluidic device using laser

micro-welding process in which the two glass plates are permanently bonded together without using any adhesives nor intermediate layer [33], C) SEM image of a 500nm diameter silica micro/nanofibre (MNF)

tied into a ring and placed on a 60µm diameter human hair, with the MNF often used for optical sensors [34], D) Intertwined microfluidic spiral channels in fused silica glass with a channel

width of 74µm, which is filled with dyes (scale: 140µm) [34], E) Quartz glass chip for cell sorting application with a dimension of 34mm × 12 mm × 2mm, fabricated by selective laser-induced etching [35], F) Top and side view of a nested nozzle in quartz glass for biological application (diameter: 10mm, height: 7mm), fabricated by selective laser-induced etching [35], G) Quartz glass connector for capillary electrophoresis, diameter 15mm, thickness 2mm, fabricated by selective laser-induced etching [35] H) Transparent suspended microchannel resonator (SMR) in fused silica with fluidic channels with a cross-section around 10µm x 5µm flowing underneath [36], I) Monolithic 3D micromixer with an impeller for glass microfluidic systems using selective laser-induced etching [37], J) Microfluidic mixer with 5 inlets and 1 outlet (channels diameter of 100µm) [38], K) Passive compliant tool for retinal vein cannulation (RVC) that relies on a buckling mechanical principle [39], L) 3D complex lab-on-a-chip (smallest channel diameter of 3µm) [38], M) Optically transparent glass micro-actuator fabricated by femtosecond laser exposure and chemical etching (missing reference), N) 3D microfluidic channel fabricated by using selective laser-assisted etching [40].

Figure 1. Different 3D miniature devices and monolithic microstructure fabricated in glass A) Volumetric 3D printing of silica glass with microscale computed axial lithography to

fabricate a 3D transparent and complex microfluidic structure, having trusses and lattice with minimum feature sizes of 50µm, [32], B) Microfluidic device using laser

micro-welding process in which the two glass plates are permanently bonded together without using any adhesives nor intermediate layer [33], C) SEM image of a 500nm diameter silica micro/nanofibre (MNF)

tied into a ring and placed on a 60µm diameter human hair, with the MNF often used for optical sensors [34], D) Intertwined microfluidic spiral channels in fused silica glass with a channel

width of 74µm, which is filled with dyes (scale: 140µm) [34], E) Quartz glass chip for cell sorting application with a dimension of 34mm × 12 mm × 2mm, fabricated by selective laser-induced etching [35], F) Top and side view of a nested nozzle in quartz glass for biological application (diameter: 10mm, height: 7mm), fabricated by selective laser-induced etching [35], G) Quartz glass connector for capillary electrophoresis, diameter 15mm, thickness 2mm, fabricated by selective laser-induced etching [35] H) Transparent suspended microchannel resonator (SMR) in fused silica with fluidic channels with a cross-section around 10µm x 5µm flowing underneath [36], I) Monolithic 3D micromixer with an impeller for glass microfluidic systems using selective laser-induced etching [37], J) Microfluidic mixer with 5 inlets and 1 outlet (channels diameter of 100µm) [38], K) Passive compliant tool for retinal vein cannulation (RVC) that relies on a buckling mechanical principle [39], L) 3D complex lab-on-a-chip (smallest channel diameter of 3µm) [38], M) Optically transparent glass micro-actuator fabricated by femtosecond laser exposure and chemical etching (missing reference), N) 3D microfluidic channel fabricated by using selective laser-assisted etching [40].

Figure 1 presents some of the 3D miniaturized and monolithic devices in the literature that are fabricated with glass using different approaches. Figure 1A show the possibility of 3D volumetric additive manufacturing of silica glass with microscale computed axial lithography for microstructures with minimum feature sizes of 50µm. It is also possible to use a maskless approach to fabricate in glass by laser micro-welding which usually involves non-adhesive bonding of two pre-printed surfaces (see Fig. 1B) The case of 500 nm diameter silica micro/nanofibre for optical sensors, which is fabricated by taper-drawing glass fiber at high temperature is presented in Fig. 1C. It is also possible to fabricate arbitrary 3D suspended hollow microstructures in transparent fused silica glass using stereolithography as shown in Fig. 1D. Using selective laser-induced etching, this presents the most predominant approach which is used from Fig. 1E to Fig. 1N, for designing different complex 3D monolithic micro-structures in a glass.

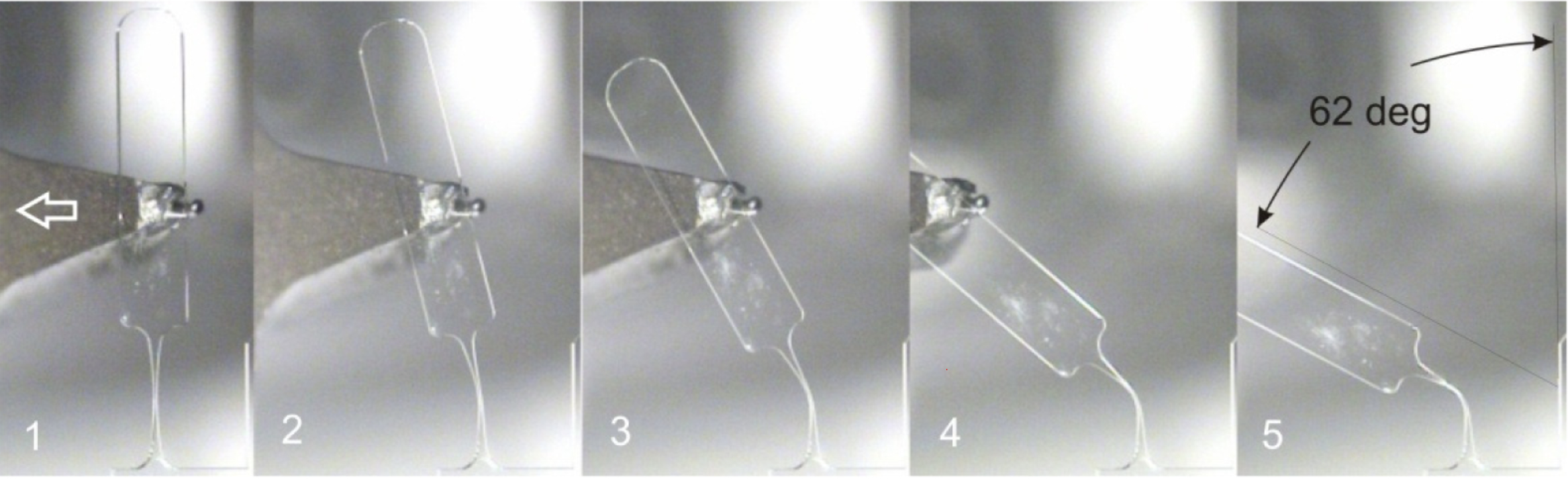

Figure 2. {Illustration of glass beam bending experiments undergoing several stress deformation for loading and unloading without breaking~

(see video). The beam is characterized by a 40µm thick flexure in its thinnest part, Image~\copyright~2011 Optical Society of America [41].

Figure 2. {Illustration of glass beam bending experiments undergoing several stress deformation for loading and unloading without breaking~

(see video). The beam is characterized by a 40µm thick flexure in its thinnest part, Image~\copyright~2011 Optical Society of America [41].

While conventional glass at the macro scale is rigid and brittle, conversely, at the micro-scale level, thin glass is flexible with high tensile strength [42], [43]. These inherent properties of glass on a micro-scale are beneficial in the design of miniaturized 3D structures. Therefore, one can take advantage of glass at the micro-scale to design and fabricate miniaturized flexible microstructure [34]. Consequently, this solidifies the possibility of designing and fabricating a continuum robot using thin glass. Moreover, for CTRs, higher dexterity in a tightly confined region requires a small radius of curvature [44]. For this reason, we ask the question of whether tubes made of glass, with a sub-millimeter diameter can permit a small radius of curvature without breaking. The proposed glass for the robot design is fused silica. Its surface stress can significantly be reduced by using a protective polymer coating, which is common in optics fiber to increase its mechanical rigidity. In addition, its mechanical strength can be further improved by minimizing the flaws in glass and enabling a low surface area because a small size limits the risk of the presence of flaws [45], [46], [41]. All these factors guarantee the ability of capillary glass to withstand high bending stress (see Fig. 2}). It also allows the capillary glass to have flexibility similar to the spring steel. Fused silica has a non-linear elastic property and the applied strain determines the elastic modulus [47],[48], with the maximum bend radius of curvature, deduced by considering tensile strength in the equation below.

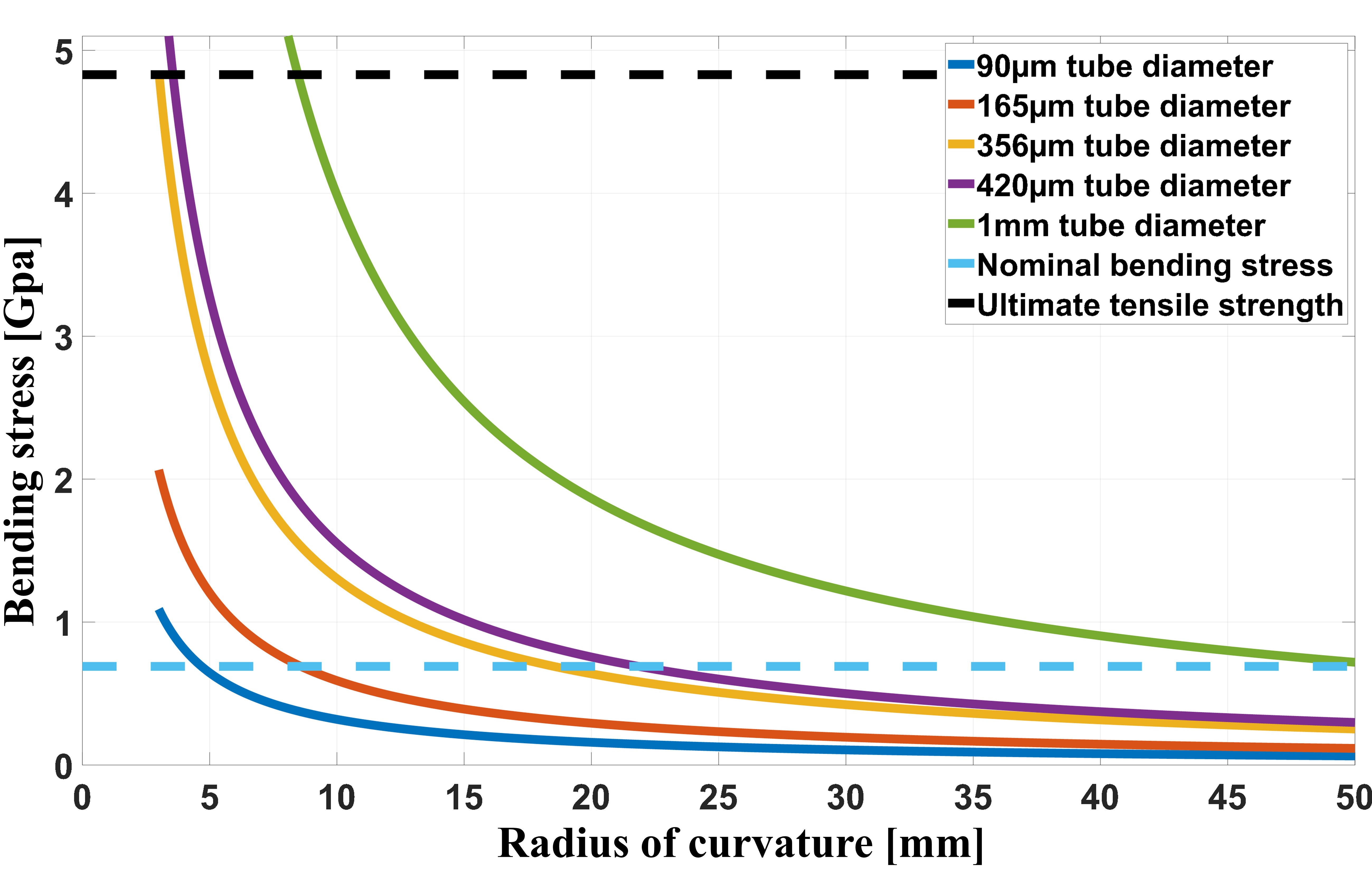

Figure 3. The relationship between the glass capillary bending stress and the obtainable bend radius of curvature for the glass diameters.

Figure 3. The relationship between the glass capillary bending stress and the obtainable bend radius of curvature for the glass diameters.

\(\sigma\) is the surface stress, \(E_o\) is Young’s modulus at zero strain (70GPa), \(r_c\) is the capillary radius, and \(r\) is the bending radius of curvature. \(\alpha=2.30\) and \(\beta=8.48\) are the second-order and third-order nonlinear material coefficients, respectively.

For the proposed miniaturized CTR, when considering the glass tube diameters used, the relationship between their bending stress and the obtainable radius of curvature, as derived using the equation above is presented in Fig. 3. % Although theoretically, the ultimate tensile strength of fused silica can reach 4.83GPa (green dash line), we considered nominal bending stress of 0.69GPa (black dash line); this consideration is in line with the Polymicro proof test Polymicro Technologies. The figure explains why it was possible to obtain a small bend radius of curvature in glass down to 5mm with tube diameter below 440µm (full detail discussed next), which is very flexible to sustain bending stress below nominal value without fracture. This is highlighted and considered as our target area in Fig. 3. Considering its ultimate tensile strength, the figure indicates that it can withstand more stress in cases of path contact during deployment and manipulation. % For both glass and Nitinol, the precurvature limits, or the obtainable minimum radius of curvature, depend on the available tube diameter; a smaller tube diameter guarantees a smaller radius of curvature without plastic deformation. Fig. 3 also demonstrated that it is theoretically possible for a 1mm glass tube to sustain bending stress over a 10mm radius of curvature like that of Nitinol, which has a minimum radius of curvature of 15 mm in literature [49]. The various approach explored to obtain a pre-curved tube using thin glass for the proposed miniaturized concentric tube robot (CTR) is discussed in detail in the subsequent blog post. Whereas for the parallel continuum robot (PCR), a standard optical fiber was used directly for the robot modeling, design, and experimental prototype, which is detailed in another blog post below. Overall, we demonstrated the possibility to actualize the first of its type, a miniaturized continuum robot using glass material. This landmark achievement and scientific breakthrough has huge prospects in the robotics and material domain as regards microsurgery or micromanipulations.

References

- 1. Tay F, Iliescu C, Jing J, Miao J: Defect-free wet etching through Pyrex glass using Cr/Au mask. Microsystem Technologies 2006, 12:935–939.

- 2. Takahashi S, Horiuchi K, Tatsukoshi K, Ono M, Imajo N, Mobely T: Development of Through Glass Via (TGV) formation technology using electrical discharging for 2.5/3D integrated packaging. In 2013 IEEE 63rd Electronic Components and Technology Conference. . 2013:348–352.

- 3. Tang T, Yuan Y, Yalikun Y, Hosokawa Y, Li M, Tanaka Y: Glass based micro total analysis systems: Materials, fabrication methods, and applications. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2021, 339:129859.

- 4. Cheng Y, Sugioka K, Midorikawa K, Masuda M, Toyoda K, Kawachi M, Shihoyama K: Control of the cross-sectional shape of a hollow microchannel embedded in photostructurable glass by use of a femtosecond laser. Opt Lett 2003, 28:55–57.

- 5. Kikutani Y, Horiuchi T, Uchiyama K, Hisamoto H, Tokeshi M, Kitamori T: Glass microchip with three-dimensional microchannel network for 2 × 2 parallel synthesis. Lab on a chip 2002, 2:188–92.

- 6. Hnatovsky C, Taylor RS, Simova E, Pattathil R, Rayner DM, Bhardwaj V, Corkum PB: Fabrication of Microchannels in Glass Using Focused Femtosecond Laser Radiation and Selective Chemical Etching. Applied Physics A 2006, 84:47–61.

- 7. Rosa HG, Gomes JCV, Souza EAT de: Transfer of an exfoliated monolayer graphene flake onto an optical fiber end face for erbium-doped fiber laser mode-locking. 2D Materials 2015, 2:031001.

- 8. Karnaushkin P, Konstantinov Y: An Experimental Technique for Aligning a Channel Optical Waveguide with an Optical Fiber Based on Reflections from the Far End of the Waveguide. Instruments and Experimental Techniques 2021, 64:709–714.

- 9. Kronig L, Hörler P, Kneib J-P, Bouri M: Design and performances of an optical metrology system to test position and tilt accuracy of fiber positioners . In Advances in Optical and Mechanical Technologies for Telescopes and Instrumentation III. Edited by Navarro R, Geyl R. SPIE; 2018:107066B.

- 10. Mittholiya K, Anshad P, Mallik A, Bhardwaj S, Hegde A, Bhatnagar A, Bernard R, Dharmadhikari J, Mathur D, Dharmadhikari A: Inscription of waveguides and power splitters in borosilicate glass using ultrashort laser pulses. Journal of Optics 2016, doi:10.1007/s12596-016-0375-9.

- 11. Niza ME, Komori M, Nomura T, Yamaji I, Nishiyama N, Ishida M, Shimizu Y: Test rig for micro gear and experimental analysis on the meshing condition and failure characteristics of steel micro involute gear and metallic glass one. Mechanism and Machine Theory 2010, 45:1797–1812.

- 12. Montanero J, Gañán-Calvo A, Acero A, Vega E: Micrometer glass nozzles for flow focusing. Journal of Micromechanics and Microengineering 2010, 20:075035.

- 13. Eklund EJ, Shkel AM, Knappe S, Donley E, Kitching J: Glass-blown spherical microcells for chip-scale atomic devices. Sensors and Actuators A: Physical 2008, 143:175–180.

- 14. Wang D, Shi T, Pan J, Liao G, Tang Z, Liu L: Finite element simulation and experimental investigation of forming micro-gear with Zr–Cu–Ni–Al bulk metallic glass. Journal of Materials Processing Technology 2010, 210:684–688.

- 15. Lenssen B, Bellouard Y: Optically transparent glass micro-actuator fabricated by femtosecond laser exposure and chemical etching. Applied Physics Letters 2012, 101.

- 16. Hata S, Sato K, Shimokohbe A: Fabrication of thin film metallic glass and its application to microactuators. In Device and Process Technologies for MEMS and Microelectronics. Edited by Chau KH, Dimitrijev S. SPIE; 1999:97–108.

- 17. Wang S, Sun D, Hata S, Sakurai J, Shimokohbe A: Fabrication of thin film metallic glass (TFMG) pipe for a cylindrical ultrasonic linear micro-actuator. Sensors and Actuators A: Physical 2009, 153:120–126.

- 18. Minami K, Kawamura S, Esashi M: Fabrication of distributed electrostatic micro actuator (DEMA). Journal of Microelectromechanical Systems 1993, 2:121–127.

- 19. Sakurai J, Hata S: Characteristics of Ti-Ni-Zr Thin Film Metallic Glasses / Thin Film Shape Memory Alloys for Micro Actuators with Three-Dimensional Structures. International Journal of Automation Technology 2015, 9:662–667.

- 20. Kometani R, Morita T, Watanabe K, Hoshino T, Kondo K, Kanda K, Haruyama Y, Kaito T, Fujita J-ichi, Ishida M, et al.: Nanomanipulator and actuator fabrication on glass capillary by focused-ion-beam-chemical vapor deposition. Journal of Vacuum Science & Technology B: Microelectronics and Nanometer Structures Processing, Measurement, and Phenomena 2004, 22:257–263.

- 21. Füzesi F, Jornod A, Thomann P, Plimmer MD, Dudle G, Moser R, Sache L, Bleuler H: An electrostatic glass actuator for ultrahigh vacuum: A rotating light trap for continuous beams of laser-cooled atoms. Review of Scientific Instruments 2007, 78.

- 22. Lin J, Brown CW: Sol-gel glass as a matrix for chemical and biochemical sensing. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry 1997, 16:200–211.

- 23. Waltermann C, Baumann AL, Bethmann K, Doering A, Koch J, Angelmahr M, Schade W: Femtosecond laser processing of evanescence field coupled waveguides in single mode glass fibers for optical 3D shape sensing and navigation. In Fiber Optic Sensors and Applications XII. Edited by Pickrell G, Udd E, Du HH. SPIE; 2015:948011.

- 24. Zusman R, Rottman C, Ottolenghi M, Avnir D: Doped sol-gel glasses as chemical sensors. Journal of Non-Crystalline Solids 1990, 122:107–109.

- 25. Rogers T, Kowal J: Selection of glass, anodic bonding conditions and material compatibility for silicon-glass capacitive sensors. Sensors and Actuators A: Physical 1995, 46:113–120.

- 26. Gao S-lin, Zhuang R-C, Zhang J, Liu J-W, Mäder E: Glass Fibers with Carbon Nanotube Networks as Multifunctional Sensors. Advanced Functional Materials 2010, 20:1885–1893.

- 27. He F, Liao Y, Lin J, Song J, Qiao L, Cheng Y, Sugioka K: Femtosecond Laser Fabrication of Monolithically Integrated Microfluidic Sensors in Glass. Sensors 2014, 14:19402–19440.

- 28. Vlasov YG, Bychkov EA, Legin AV: Chalcogenide glass chemical sensors: Research and analytical applications. Talanta 1994, 41:1059–1063.

- 29. Gharbi A, Kallel AY, Kanoun O, Cheikhrouhou-Koubaa W, Contag CH, Antoniac I, Derbel N, Ashammakhi N: A Biodegradable Bioactive Glass-Based Hydration Sensor for Biomedical Applications. Micromachines 2023, 14.

- 30. Butt MA, Voronkov GS, Grakhova EP, Kutluyarov RV, Kazanskiy NL, Khonina SN: Environmental Monitoring: A Comprehensive Review on Optical Waveguide and Fiber-Based Sensors. Biosensors 2022, 12.

- 31. Zhang J, Xiang Y, Wang C, Chen Y, Tjin SC, Wei L: Recent Advances in Optical Fiber Enabled Radiation Sensors. Sensors 2022, 22.

- 32. Toombs JT, Luitz M, Cook CC, Jenne S, Li CC, Rapp BE, Kotz-Helmer F, Taylor HK: Volumetric additive manufacturing of silica glass with microscale computed axial lithography. Science 2022, 376:308–312.

- 33. Wlodarczyk K, Hand D, Maroto-Valer M: Maskless, rapid manufacturing of glass microfluidic devices using a picosecond pulsed laser. Scientific Reports 2019, 9:20215.

- 34. Tong L: Micro/Nanofibre Optical Sensors: Challenges and Prospects. Sensors 2018, 18.

- 35. Gottmann J, Hermans M, Repiev N, Ortmann J: Selective Laser-Induced Etching of 3D Precision Quartz Glass Components for Microfluidic Applications—Up-Scaling of Complexity and Speed. Micromachines 2017, 8.

- 36. FEMTOprint: Transparent Suspended Microchannel Resonator. FEMTOprint News 2018,

- 37. Kim S, Kim J, Joung Y-H, Ahn S, Park C, Choi J, Koo C: Monolithic 3D micromixer with an impeller for glass microfluidic systems. Lab on a Chip 2020, 20.

- 38. FEMTOprint: Standardisation of microfluidics. Opportunity for innovative technologies. FEMTOprint News 2017,

- 39. FEMTOprint: How three-dimensional thinking is turning a piece of material into smart medical devices. FEMTOprint News 2018,

- 40. FEMTOprint: FEMTOprint TESTIMONIALS. FEMTOprint News 2023,

- 41. Bellouard Y: On the bending strength of fused silica flexures fabricated by ultrafast lasers (Invited). Opt Mater Express 2011, 1:816–831.

- 42. Rafael S Ribeiro, Louter C, Klein T: Flexible transparency: A study on thin glass adaptive façade panels. In Challenging Glass 6 - Conference on Architectural and Structural Applications of Glass, TU Delft, Netherlands. . 2016:135–148.

- 43. Garner SM, Li X, Huang ming-H: Introduction to Flexible Glass Substrates. In Flexible Glass. . John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2017:1–33.

- 44. Chikhaoui MT, Rabenorosoa K, Andreff N: Kinematics and performance analysis of a novel concentric tube robotic structure with embedded soft micro-actuation. Mechanism and Machine Theory 2016, 104:234–254.

- 45. Tomozawa M: Fracture of Glasses. Annual Review of Materials Science 1996, 26:43–74.

- 46. Wondraczek L, Bouchbinder E, Ehrlicher A, Mauro J, Sajzew R, Smedskjaer M: Advancing the Mechanical Performance of Glasses: Perspectives and Challenges. Advanced Materials 2022, 34:2109029.

- 47. Barker LM, Hollenbach RE: Shock-Wave Studies of PMMA, Fused Silica, and Sapphire. Journal of Applied Physics 1970, 41:4208–4226.

- 48. Matthewson MJ: Optical fiber mechanical testing techniques. In Fiber Optics Reliability and Testing: A Critical Review. Edited by Paul DK. SPIE; 1993:34–61.

- 49. Sears P, Dupont P: A Steerable Needle Technology Using Curved Concentric Tubes. In IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems. . 2006:2850–2856.