To further enhance MIS capabilities, there is a growing demand for smaller and more precise devices.

Considering the most popular commercial surgical robotic system, which is da Vinci.

It has more than 10 million MIS performed worldwide [1],[2],[3],[4]. This surgical robot uses instruments that are rigid and straight with articulating tips.

In addition, they also have a large footprint in the operating room. Hence, the trend toward miniaturization of MIS tools is evident in order to maximize the benefits and advantages that come with it [5].

Some of the key benefits or reasons for MIS device miniaturization include:

- Enable less invasive procedures: With smaller devices, surgeons can perform interventions through smaller incisions or natural orifices, minimizing tissue damage and reducing patient trauma. This approach results in faster healing times, shorter hospital stays, and improved patient outcomes.

- Need for improved dexterity: The availability of highly specialized instruments and devices allows surgeons to perform tasks swiftly with a high level of dexterity and reliability. Indeed, miniaturized devices can navigate intricate anatomical structures, enabling surgeons to access challenging areas that were previously difficult to reach. For example, transcatheter procedures like aortic valve replacement can now be performed entirely from a groin-area access site [6],[7],[8], thanks to miniaturized devices.

- Easy patient-specific adaptability: In all cases, due to the fact that at the same scale, one has to adapt to the anatomy, this benefits by having a smaller device that can easily be customized to adapt patient-specific need or anatomy structure. There is a higher benefit/possibility of organ collision avoidance using a miniaturized MIS device.

- Cost reduction and improvement of patient comfort: Smaller devices require fewer resources and materials, resulting in cost savings in manufacturing and medical procedures. Additionally, the use of miniaturized devices can contribute to reduced pain, scarring, and discomfort for patients, enhancing their overall experience during and after surgery.

As technology advances, the convergence of various aspects is expected to drive development in terms of smaller, more dexterous, and less expensive devices for a wide range of procedures. The ongoing improvements in MIS device miniaturization are vital for pushing the boundaries of what is possible in surgical interventions, ultimately leading to enhanced patient care and outcomes. Therefore, having manipulators that are scalable to a small size, flexible yet strong, and capable of reaching difficult-to-access surgical sites via complex pathways and completing the surgical task with dexterity would be extremely beneficial. Continuum robots with small sizes are more suitable for MIS compared to using straight rigid instruments [9]. Although, among all the different types of medical robots, the continuum robot has witnessed a sporadic rise in research and the highest publication throughput currently. Yet, one major aspect of research and need in the field of medicine that was identified was the area of miniaturization [5]. In as much the importance of robots in medicine is undoubtedly overemphasized, there are still large areas calling for a research breakthrough, especially in microsurgery and micromanipulation.

Miniaturized manipulators are designed to manipulate small objects with a high degree of accuracy and repeatability in confined spaces. These devices have a wide range of applications in different fields, such as the manipulation of samples inside scanning electron microscopes (SEM) or for endoscopic medical procedures. For endoscopic medical procedures, the manipulators are inserted into the body through small incisions and are used to perform delicate procedures, such as imaging, biopsy, suturing, or removing small tissue samples. Inside SEM, miniaturized manipulators are used for handling samples for imaging, performing various measurements, or assembling components. One of the current challenges of micromanipulation e.g in SEM or medical is to increase the dexterity of the manipulators by integrating rotations at the distal end, to actualize tool orientation with large angles. Indeed, the three translational movements of the end-effector in the x, y, and z axis, can be generated by proximal joints, whereas only distal ones can produce the orientation of the tool. Having a distal orientation section is well known to improve manipulator dexterity [10],[11],[12],[13].

When considering parallel manipulators, which has many advantages such as high precision, high speed, high payload/force capabilities, and extrinsic actuation, that enable locating the actuators outside of the confined space leading to a very high miniaturization potential but they are often limited in workspace volume [14]. Presently, the smallest parallel manipulators in the literature include Millidelta [15] and Migribot [16]. Though each presents key benefits thanks to their parallel configurations, they are both restricted to translative motion. Conversely, this issue and limitation can be solved using a new type of parallel robot called parallel continuum robots (PCRs) [17]. For this reason, added to the benefits and possibilities of using flexible glass at a small scale, this is one of the key research investigations and analyses in this dissertation.

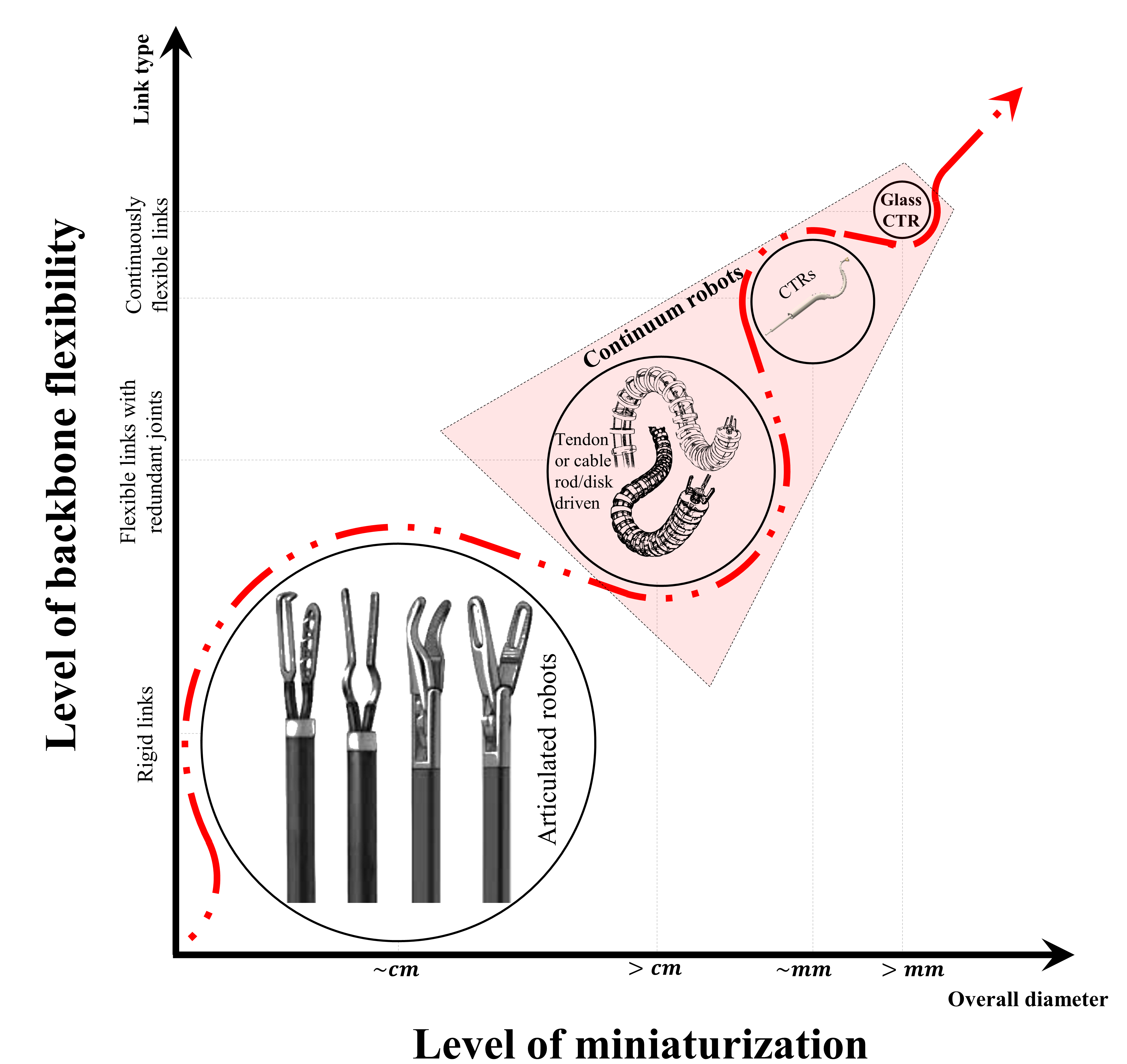

Figure 1. Trend in medical robotic devices with a paradigm shift from rigid link/articulated robots to continuum robots on the bases of backbone flexibility and level of miniaturization.

Figure 1. Trend in medical robotic devices with a paradigm shift from rigid link/articulated robots to continuum robots on the bases of backbone flexibility and level of miniaturization.

Current MIS tools still have challenges to access some confined regions of surgical sites due to the size, location, or sensitivity/complexity nature of anatomical structure e.g. when considering the use of the conventional rigid straight instrument. Considering the trend in medicine for further miniaturization, which targets the possibility of accessing hard-to-reach zone of interest. In fact, the rising trend in medicine for micro-port multi-deployment strategy has given rise to the need for the development of devices that can meet the demand, especially in neurosurgery. The ongoing advancements in MIS device miniaturization contribute to the evolution of surgical techniques, offering numerous benefits to patients and healthcare providers alike. In general, the need for miniaturization has motivated the rise in small-scale smart devices, which are proposed for microsurgery or MIS, and has paved the way for the high research throughput in compact continuum robots. The trend for further miniaturization with its benefits, has put continuum robots on top of the ladder among clinical instruments and devices for MIS (refer to Fig. 1).

In Fig. 1, concentric tube robots (CTRs) are at the top of the ladder when considering the level of backbone flexibility due to no redundant joint by disk. In the case of miniaturization, they are simply composed of nested pre-curved tubes that can be easily scaled down sub-millimeter level. Considering the conventional use of Nitinol for continuum robot fabrication, which is now the predominant material for prototyping different continuum robots in the literature. However, researchers had reached a stagnating point of constant use of Nitinol and then began to call for investigation of other viable materials [18]. These paved the way for the use of 3D print materials but unfortunately, the process is highly dependent on the printer setting, and output or mechanical qualities were poor compared to the use of Nitinol. To that effect and in regard to the present demand for further miniaturization, we considered and explored the use of glass at a small scale for the fabrication of miniaturized continuum robots. Since thin glass at a small scale is flexible e.g. optical fiber, this presents great benefits considering the inherent properties of glass like the light carry capacity, and this will open entirely new doors in the domain of continuum robots along with the application potentials.

References

- 1. Badani K, Kaul S, Menon M: Evolution of robotic radical prostatectomy - Assessment after 2766 procedures. Cancer 2007, 110:1951–8.

- 2. D’Ettorre C, Mariani A, Stilli A, Baena F Rodriguez y, Valdastri P, Deguet A, Kazanzides P, Taylor RH, Fischer GS, DiMaio SP, et al.: Accelerating Surgical Robotics Research: A Review of 10 Years With the da Vinci Research Kit. IEEE Robotics & Automation Magazine 2021, 28:56–78.

- 3. Marcus HJ, Hughes-Hallett A, Cundy TP, Yang G-Z, Darzi A, Nandi D: Da vinci robot-assisted Keyhole Neurosurgery: A cadaver study on feasibility and safety. Neurosurgical Review 2014, 38:367–371.

- 4. Intuitive: Intuitivecom 2021,

- 5. Yang G-Z, Bellingham J, Dupont PE, Fischer P, Floridi L, Full R, Jacobstein N, Kumar V, McNutt M, Merrifield R, et al.: The grand challenges of Science Robotics. Science robotics 2018, 3:eaar7650.

- 6. Onan B: Minimal access in cardiac surgery. The Turkish Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery 2020, 28:708–724.

- 7. Kalogeropoulos AS, Redwood SR, Allen CJ, Hurrell H, Chehab O, Rajani R, Prendergast B, Patterson T: A 20-year journey in transcatheter aortic valve implantation: Evolution to current eminence. Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine 2022, 9.

- 8. Toggweiler S, Leipsic J, Binder RK, Freeman M, Barbanti M, Heijmen RH, Wood DA, Webb JG: Management of Vascular Access in Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement: Part 1: Basic Anatomy, Imaging, Sheaths, Wires, and Access Routes. JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions 2013, 6:643–653.

- 9. Burgner J Kahrs, Rucker DC, Choset H: Continuum Robots for Medical Applications: A Survey. IEEE Transactions on Robotics 2015, 31:1261–1280.

- 10. Wu L, Crawford R, Roberts J: Dexterity Analysis of Three 6-DOF Continuum Robots Combining Concentric Tube Mechanisms and Cable-Driven Mechanisms. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters 2017, 2:514–521.

- 11. Chikhaoui MT, Rabenorosoa K, Andreff N: Kinematics and performance analysis of a novel concentric tube robotic structure with embedded soft micro-actuation. Mechanism and Machine Theory 2016, 104:234–254.

- 12. Peyron Q, Boehler Q, Rougeot P, Roux P, Nelson BJ, Andreff N, Rabenorosoa K, Renaud P: Magnetic concentric tube robots: Introduction and analysis. The International Journal of Robotics Research 2022, 41:418–440.

- 13. Li Z, Wu L, Ren H, Yu H: Kinematic comparison of surgical tendon-driven manipulators and concentric tube manipulators. Mechanism and Machine Theory 2017, 107:148–165.

- 14. Jin Y, Chanal H, Paccot F: Parallel Robots. In Handbook of Manufacturing Engineering and Technology. . Springer London; 2015:2091–2127.

- 15. McClintock H, Temel FZ, Doshi N, Koh J-sung, Wood RJ: The milliDelta: A high-bandwidth, high-precision, millimeter-scale Delta robot. Science Robotics 2018, 3.

- 16. Leveziel M, Haouas W, Laurent GJ, Gauthier M, Dahmouche R: MiGriBot: A miniature parallel robot with integrated gripping for high-throughput micromanipulation. Science Robotics 2022, 7:eabn4292.

- 17. Bryson CE, Rucker DC: Toward parallel continuum manipulators. In 2014 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA). . IEEE; 2014:778–785.

- 18. Gilbert HB, Rucker DC, Webster III RJ: Concentric Tube Robots: The State of the Art and Future Directions. In Robotics Research. . Robotics Research. Springer Tracts in Advanced Robotics; 2016:253–269.